Exorcism Theater

What Happens When Power Can No Longer Enforce Consensus Quietly

Tim Pool’s recent hysteria feels like an ice pick in the brain.

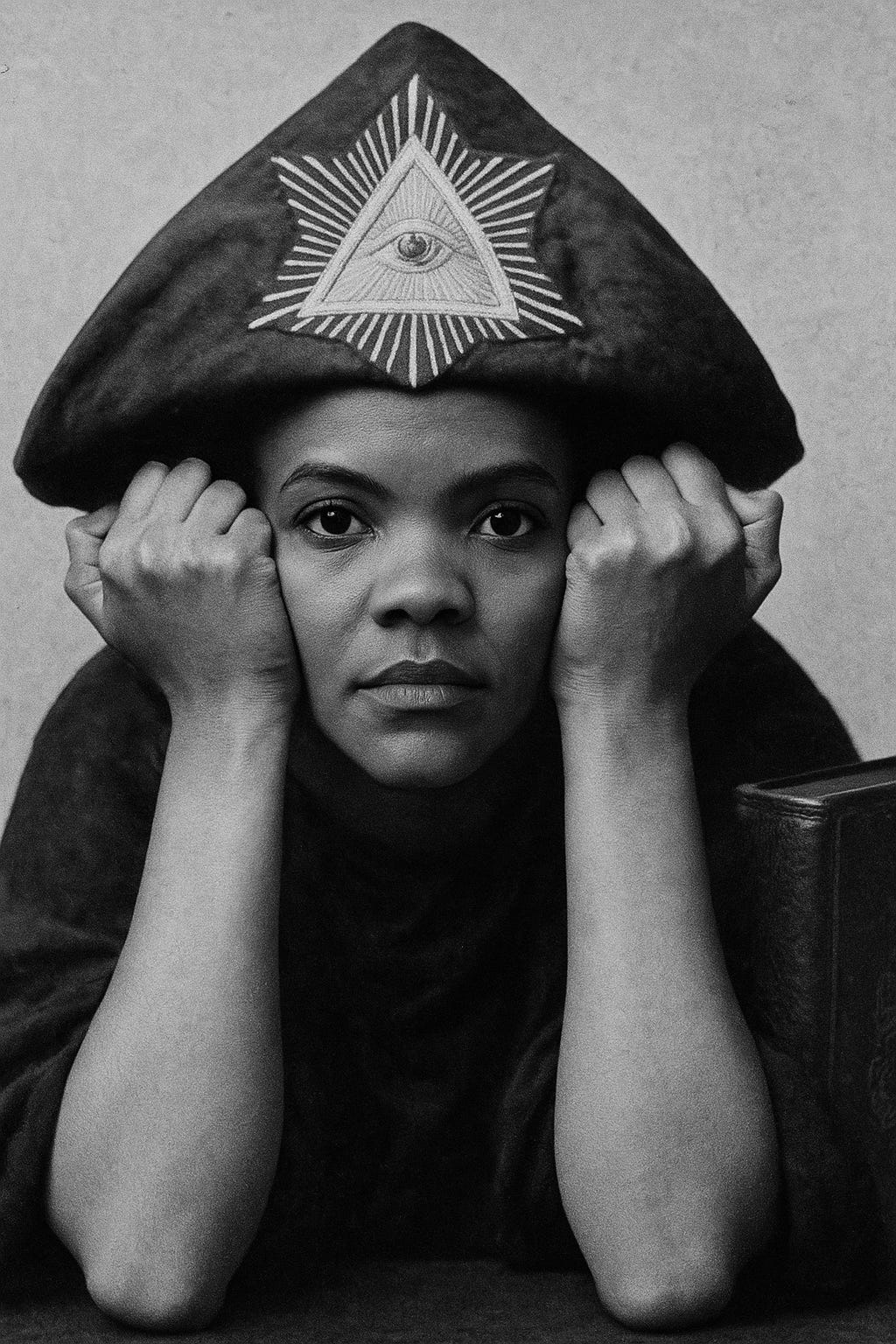

I stopped watching him years ago because the tone became unbearable. And yet, despite actively avoiding him, his latest diatribe is impossible to escape. The whiny, desperate, hyperbolic attack on Candace Owens is everywhere. The volume alone demands attention, as if the performance itself is meant to overwhelm discernment.

Pool doesn’t persuade. He grabs attention—and reactivity is the hook. This is not strength. It is what power looks like when it senses loss of control.

What struck me wasn’t how extreme it felt—but how familiar. Familiar not in a contemporary way, but in a historically precise one. This is the sound power makes when it is no longer confident it can enforce consensus quietly.

It reminded me of something Lon Milo DuQuette mentioned to me years ago. Or rather, someone. A figure from another era, operating under a different moral banner, but animated by the same psychic mechanics.

The tone.

The obsession.

The insistence that this person is not merely wrong, but dangerous—corrupting, evil.

This is not analysis. It is ritualized expulsion—one of the oldest tools power reaches for when argument no longer secures obedience.

What we’re watching is less political commentary and more a nervous system in revolt: the panic response of authority confronting the possibility that it no longer commands belief, that the old spell no longer holds.

Love her or hate her, the truth is Candace Owens isn’t being argued with.

She is being ritually expelled.

And that’s the tell.

Cultures do not reserve this level of hysteria for ordinary disagreement. They unleash it when a symbolic figure threatens the coherence of the story itself—when someone breaks rank, refuses the script, or exposes the machinery behind the curtain.

This is why the attacks feel disproportionate.

This is why they are so shrill.

This is why they are everywhere.

And this is where the comparison becomes unavoidable.

Aleister Crowley occupied the same structural position in his time that Candace Owens occupies now—not because they share beliefs, but because they trigger the same response from systems under stress.

When argument fails, cultures reach for demons.

Cultures require villains and heretics because they serve a function for power. They act as pressure valves—absorbing contradictions power cannot resolve internally without questioning itself. Public shaming replaces introspection. Moral outrage substitutes for renewal. By locating the threat in a single figure, authority avoids confronting its own instability.

Every era selects its contaminant.

The irony is that hysteria always reveals more about the accuser than the accused.

When the volume goes up and the thinking goes down, what you’re witnessing is not courage—but fear, broadcast at scale.

And this is where the historical parallel stops being abstract.

Because when you place Candace Owens and Aleister Crowley side by side—not ideologically, but structurally—the pattern becomes unmistakable.

1. From “Wrong” to “Evil”

Crowley was not merely criticized. He was framed as satanic, corrupting, demonic, inhuman. The press did not stop at disagreement. It reached for metaphysical language—The Beast, the wickedest man alive, a moral pathogen.

Watch the same pattern now.

Critics of Candace Owens don’t merely say she is incorrect. They say she is:

Evil

Demonic

Poisonous

A danger to souls

And yes—the C word, deployed not as insult but as excommunication.

This is unmistakably theological language. And it is a tell.

When a culture reaches for demons, it is no longer confident in reason—it is attempting to reassert authority through moral spectacle.

2. Elite Panic Masquerading as Moral Concern

Crowley terrified the Edwardian elite not because of his magic, but because he refused containment. He could not be anchored—religiously, nationally, or morally. He moved across borders, classes, and belief systems with impunity, making authority look porous.

Owens triggers a similar response.

Her threat is not that she persuades everyone, but that she cannot be managed:

She does not submit to elite consensus

She does not accept moral tutelage

She does not soften under pressure

She does not ask forgiveness

What presents as moral outrage is often institutional panic. Elites are most alarmed not by opposition, but by figures who demonstrate that the machinery no longer works.

3. Heresy Signals a Cracking System

Heresy is not disagreement. Heresy is boundary violation.

Crowley was dangerous because he demonstrated that authority could be mocked—and survived.

Owens occupies the same space:

Deplatforming attempts fail

Condemnation amplifies her reach

Moral framing backfires

Attacks generate loyalty rather than retreat

This is the nightmare scenario for any power structure: a figure who grows stronger under censure. At that point, criticism turns theological. Evil replaces error. Demons replace arguments.

4. The Press as Ritual Enforcer (Again)

The press once acted as a moral priesthood. It still does.

Crowley was not investigated—he was exorcised:

Repetition of scandal

Simplification of narrative

Ridicule as containment

Spectacle over substance

Today’s media runs the same ritual, just faster and louder. The function has not changed:

Identify the threat.

Inflate the threat.

Mark the threat as impure.

Warn the public away.

What presents as journalism is often boundary maintenance—deciding who may speak and who must be marked.

5. Gender Sharpens the Blade

Crowley was attacked as obscene and excessive. Owens is attacked as dangerous and corrupting.

Different era. Same instinct.

A woman who refuses the sanctioned moral posture—especially one who speaks fluently, unapologetically, and without deference—provokes a level of hostility that cannot be explained by her claims alone.

The intensity of the reaction is the evidence.

Conclusion: Power Under Stress Repeats Itself

Aleister Crowley was not significant because he was right. He was significant because he revealed how power behaves under stress—loud, moralizing, punitive, and afraid.

Candace Owens now occupies that same structural position.

Calling her “the new Crowley” is not endorsement. It is an indictment of a culture so uncertain of itself that it reaches for demons instead of arguments.

And historically, that is never a sign of strength.

Power does not grow hysterical when it is strong.

It panics when it knows the spell is breaking.

The louder the exorcism, the weaker the authority behind it.

**SEASON FOUR**

## **THE LOST TECHNOLOGY OF THE GODS**

Preorder now for early access to the next evolution of Magical Egypt.

As a preorder buyer, you’re not just getting the new series early —

you’re getting **the entire archive of the journey so far as a bonus.**

Also I am sending the UNBOUND Protocol out today and it is free so if you want it …

You could add Giordano Bruno alongside Candace and Crowley.

Eloquently said.